#004 - Mystery of the seabed holes

Pockmarks or seafloor craters can reach tens of metres in diameter and be several metres deep. Described in a paper by Barrie et al (2005), these seabed holes are typically found in groups and are formed by the removal of sediment as fluid, commonly gas, escapes into the water column. Examples of pockmarks are varied across the world. On the western slope of the Norwegian Trench, elongated depressions associated with pockmarks have been related to faulting within soft, silty, unconsolidated clay sediments. Aligned pockmarks within the Ibiza Channel, in the western Mediterranean, have formed by the escape of gases and associated waters through faults from a hydrothermal field beneath the surficial sediments. Shallow submarine slides in the Eivissa Channel of the western Mediterranean Sea are associated with pockmark swarms, or regions with high fracture density.

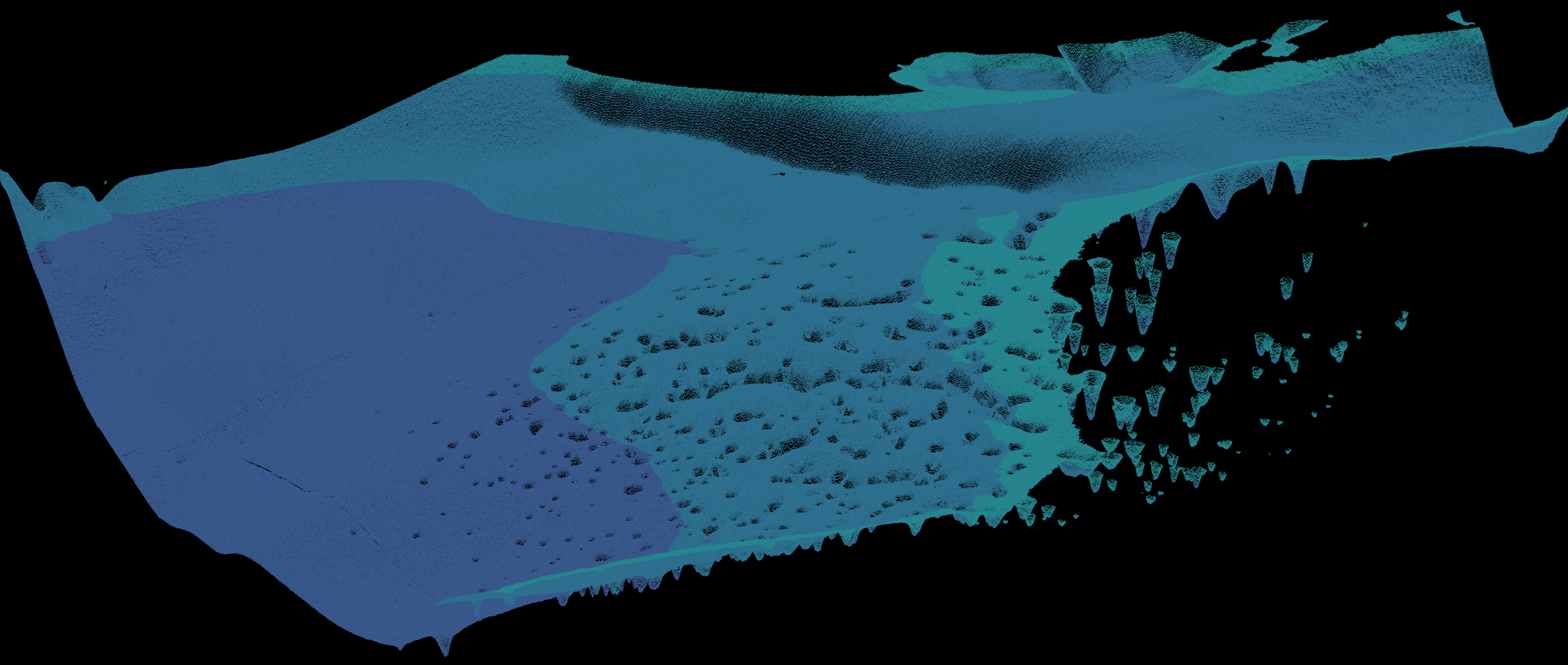

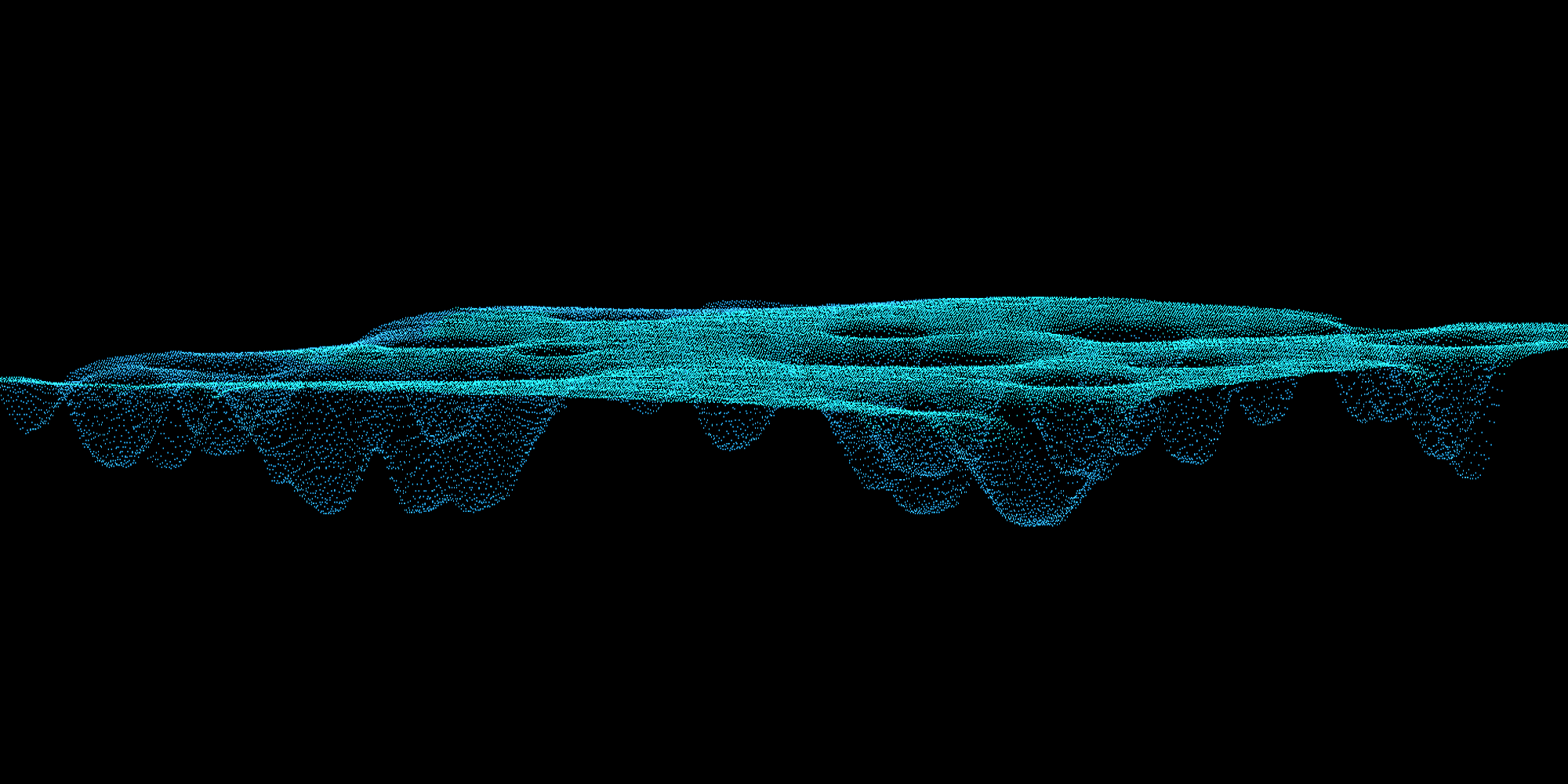

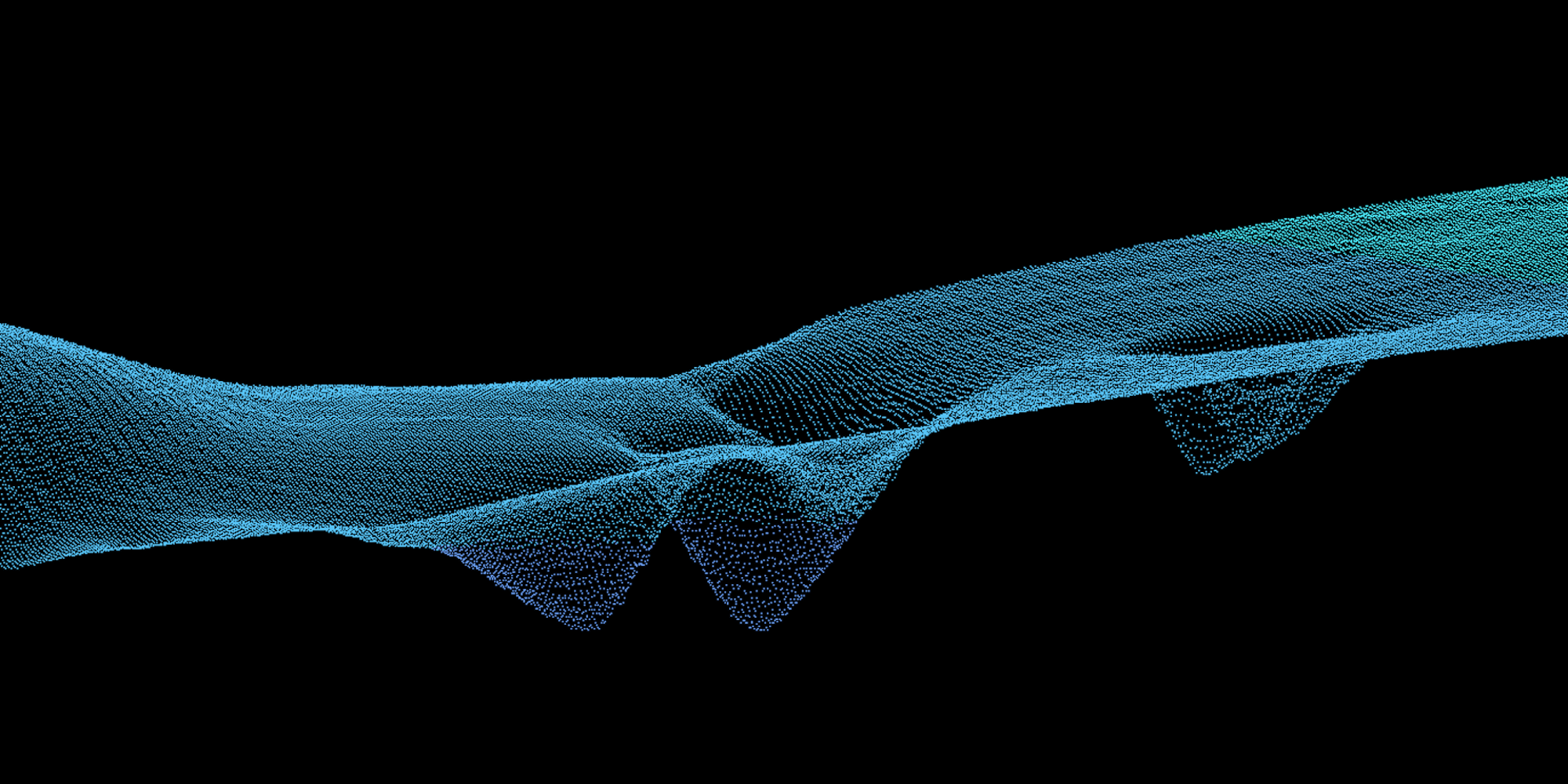

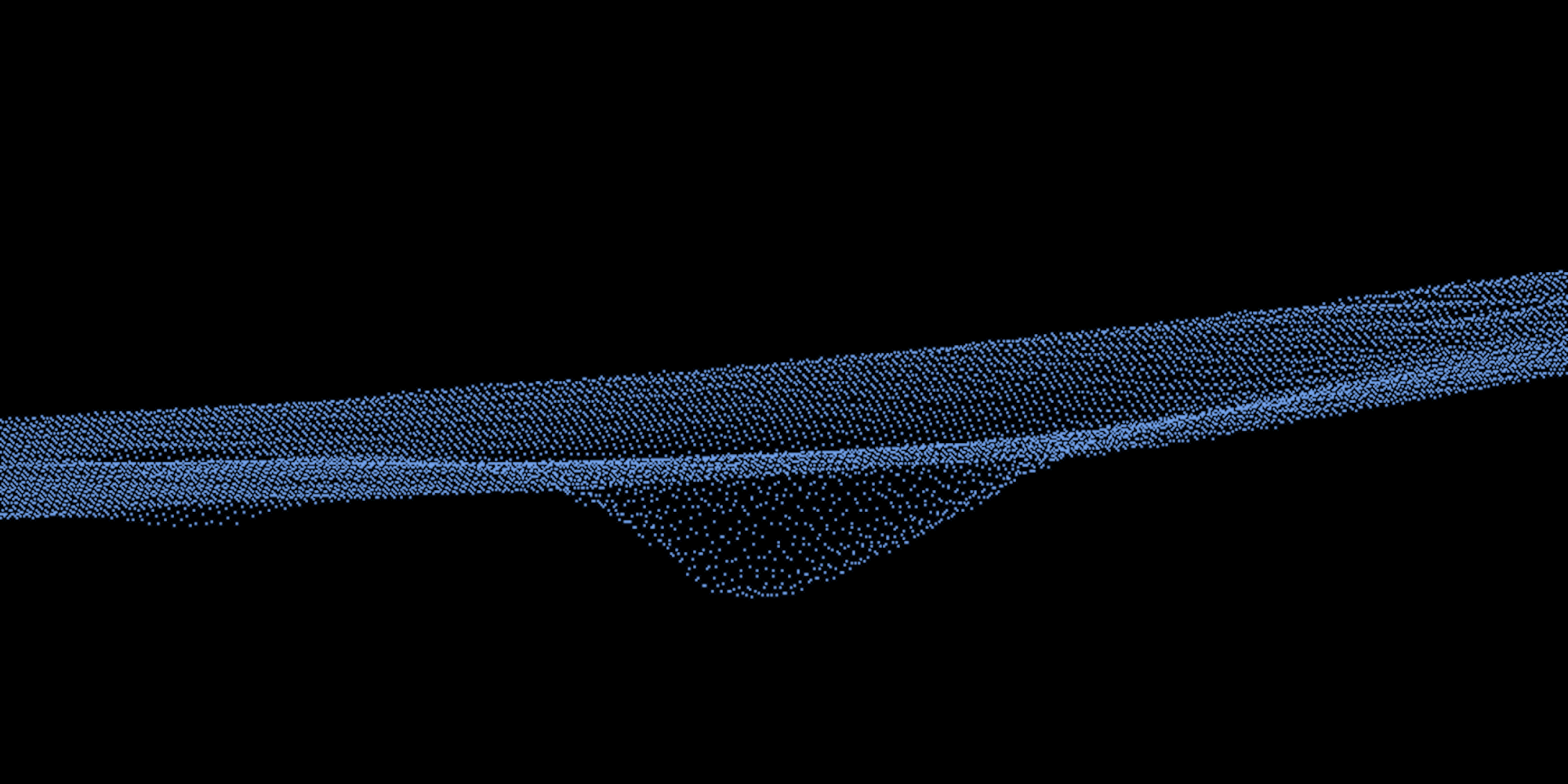

In British Columbia, the linear pockmark chains identified off the Fraser River Delta foreslope have been associated with crustal faulting. Other areas of pockmarks that show definite orientation occur in the central and northern Georgia Strait could also indicate faults. A field of up to 200 pockmarks has been discovered on the seabed of English Bay, the Outer Harbour region of Burrard Inlet. The field of underwater pockmarks is between 18 to 65 meter deep, with each hole ranging from 15 to 100 meters in diameter and between 5 to 15 meters deep at their cusp. Mostly circular, the pockmarks are in places aligned along linear traces and coalesce to form more irregular, near-linear trenches similar to the pockmarks along the nearby Fraser Delta Fault. Some pockmarks are located in designated shipping lanes for vessels approaching the Vancouver Port and others coincide with designated anchorages for large vessels waiting outside the port (Barrie et al, 2005).

The figures below are rendered using a mosaic of elevation datasets (raw data from CHS 2018) and interpolated into a regular lattice following the methods described in post “#005 - From raw data to surface lattice”.

A study presented at the 2005 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting described how multibeam and sidescan sonar surveys, high-resolution seismic profiling as well as core and water sampling were used to study the pockmark field in Outer Harbour. They found the majority of pockmarks are randomly distributed, yet some form linear chains, raising the possibility of an association with bedrock control. High resolution seismic and 3.5 kHz profiles reveal that the pockmarks formed at the top of a thick, transparent postglacial mud deposit that contains shallow gas. Piston cores taken from areas where the gas is located within 5 m of the seabed contain up to 9.5% by volume of methane. Gas is absent in some areas of highest pockmark density, suggesting that it has been efficiently vented through the pockmarks. A repeat multibeam survey showed no significant changes in pockmark distribution or dimensions over a one-year period and no active venting was observed during acoustic and video surveys, suggesting that the pockmarks must form intermittently. Given the high sedimentation rate in the bay, it is not likely that the pockmarks would remain open for long periods. It is hypothesized that the venting occurred in the recent geological past as a result of sediment liquefaction during an earthquake event, possibly the last megathrust earthquake of 1700 AD. Furthermore, the earliest maps of Burrard Inlet with bathymetric contours date back to 1920 and 1930, showing scattered holes that match modern data.

Many thanks to environmental biologist Patrick Lilley who found the information shared above:

- Barrie et al, 2005. Georgia Basin: Seabed features and marine geohazards. Environmental Marine Geoscience 4. Geoscience Canada.

- AGU, 2005. American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting. Abstract ID OS32A-03.